Jack Eisner: Holocaust “Gravestone” Fighting for Truth

- Beth Sarafraz

- May 1, 2019

- 16 min read

Updated: Mar 30, 2021

![Illustration: Warsaw Ghetto Fighters Apprehended by Nazi Troops by Unknown (Franz Konrad confessed to taking some of the photographs or photographers from Propaganda Kompanie nr 689) [Public Domain] via Wikimedia](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/599529_f824e6c2e6214abba71464493f0c3524~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_640,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/599529_f824e6c2e6214abba71464493f0c3524~mv2.jpg)

Illustration: Warsaw Ghetto Fighters Apprehended by Nazi Troops by Unknown (Franz Konrad confessed to taking some of the photographs in the Stroop Report or by photographers from Propaganda Kompanie nr 689) [Public Domain] via Wikimedia

Jack Eisner — born Jacek Zlatka in Warsaw in November 1925 — was a 19-year-old Polish Jew who weighed 80 pounds when World War II ended. He was one of the few “lucky ones” who crawled out of that inferno called the Holocaust, where Jews who did not lose their lives lost whole neighborhoods, cities, countries, continents, and worlds populated by family, friends, lovers, and every dear familiar face they had ever known.

Walking through the wreckage of such absolute scorched earth devastation, who would be surprised if survivors nearly lost their minds as well? More surprising is that individuals such as Jack Eisner did not lose their minds, the will to rebuild their lives, the determination to find some measure of personal happiness, the self-imposed duty to bear witness for all those who were silenced, and the ability to make positive contributions to society.

Eisner — who fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising until he was caught, tortured, and imprisoned in a series of concentration camps including Majdanek, Budzyn, Flossenburg, and Dachau, and who was liberated from the Nazi beasts by U.S. General Patton’s troops — learned that while the free world danced in the streets celebrating the war’s end, he and his mother Zofia — whom he had found by pure chance at a train station in Prague — were the sole survivors of their entire family.

“I am their gravestone,” he wrote in his memoir, “because I am a survivor.”

“Bearing Witness”

Back in the mid-80s, Eisner granted an interview to a young, inexperienced reporter. Having read his bestselling autobiography, "The Survivor," and having seen the movie "War and Love" based on the book — I traveled to his upscale home 27 floors above Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. There, opening the door, was an intense, middle-aged man smiling and speaking in Yiddish-accented English, who served ice cream and kosher chocolate to his guest, and who sat for an interview that would remain unpublished for many years.

Eisner, as reported in news accounts, had displayed such genius in the

business of import-export, founding and building his own company, Stafford Industries, that he was able to “retire” in 1978 — a millionaire at age 53. He had married another Holocaust survivor soon after the war’s end. The couple had children — a daughter and two sons — and then, when Eisner turned 45, they divorced.

His mission was single-minded, as he explained to me: to tell his story and the lessons of the Holocaust to the world. He would do exactly that as a book author and producer of a play and movie based on the book, with many other projects to follow:

He founded the first Institute of Holocaust Studies at the Graduate Center at CUNY and established the Holocaust Survivors Memorial Foundation.

He helped a group of friends who had fought the Nazis in Warsaw together with him to launch the Warsaw Ghetto Resistance Organization.

He visited U.S. President Gerald Ford at the White House leading a Warsaw Ghetto survivors’ delegation and put up a monument in Warsaw’s Jewish cemetery in memory of the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered by the Nazis.

He was the driving force behind the first ever Holocaust Commemoration at the Vatican with Pope John Paul II — whom he had met earlier as Bishop Karol Wojtyla in Cracow, Poland — in an attempt to improve Jewish-Christian relations via simple honest talk, as was his way.

He testified against Nazi war criminals at their trials and helped the U.S. government track down perpetrators of crimes against humanity whenever possible.

Speaking to the The Washington Post in 1983, Eisner recalled his American relatives advising him to keep quiet about what the Nazis did to him in their concentration camps: “They said, ‘It’s bad for you to talk about it.’ What they were really saying was, ‘We don’t want to listen.’”

But Jack Eisner was not the sort of man to conduct polls or surveys in order to determine whether the heart-wrenching testimony of Jewish suffering would be a “good” thing to talk about, or if anyone would even want to hear it.

Compelled and driven to action by something buried deep inside, he set

down chapter after chapter until he completed his book, "The Survivor," telling the tale of his desperate six-year fight to stay alive — 320 pages of wall-to-wall crisis and terror, published by William Morrow in 1980. In 2003, Kensington Publishing Corporation did a reprint, because readers — ordinary people, young adults who had never read a Holocaust memoir — praised it to the moon and demanded that the Amazon online shopping site restock it.

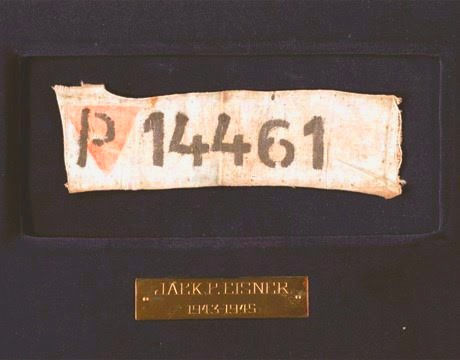

To this day, years after the 1985 interview, I still recall the cabinet in a room off of Eisner’s living room. Behind its glass door attached to the cabinet back was a piece of Jack Eisner’s concentration camp uniform pinned to a square of blue velvet, with a gold plaque under it reading: “JACK P. EISNER, 1943-1945.”

Clearly this was no ordinary rags to riches story here — this was Dachau to Manhattan, gas chamber to penthouse. The ripped piece of cloth was displayed as an item of real value — and was probably the only thing Jack Eisner had that was not ripped away from him on the day he was finally liberated, except for the memories in his head.

The backstory to the framed Holocaust insignia went like this: Working in Flossenburg, carting corpses from the gas chambers to the crematorium

under the direction of a German criminal named Karl the Stuttgarter, Eisner knew he could not hold out much longer. Luckily Karl saw some value in keeping him alive, and therefore replaced his yellow triangle bearing the letter “J” for Jew with a red triangle bearing the letter “P” for Polish Christian. The new insignia officially designated Eisner as an Aryan Christian to the camp’s SS administration. “P-14461” gave him an edge in cheating death.

Approximately 40 years later it was on display in Eisner’s luxury residence. I wondered: Did it serve as a warning never to forget that nothing is permanent, that whatever you own can be lost or seized by others at any moment? Did it serve as a physical anchor to the past, where loved ones were frozen in time, butchered more brutally than animals in the blink of an eye and gone from the world forever? Was it tangible evidence of a real life nightmare, much like the famous Ghetto Memorial in Warsaw, described by Eisner in "The Survivor" as follows:

“Yes… once there was a wall,” he told some little Polish kids who were standing around, trying to see what this grown man was staring at. He gestured to a spot a distance away, where the wall used to be. “They could not see it, but for me, it was still there. And I was still there. I am still there. I will always be there.”

The unpublished interview, together with recollections of Jack Eisner recently shared by his second wife and widow Sara, form the basis of this report. Eisner passed away in 2003, but his story lives on as testimony about one man’s unrelenting and tenacious fight for life — before, during, and after the Holocaust. Sara Eisner comments, with a smile, that his favorite song was Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.”

Teenage Resistance In The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

For young Jacek Zlatka, the war began at the age of bar mitzvah, before the boy had time to grow into the man he already was on the inside — a person of character, courage, compassion, and conviction.

Smuggling food past the vicious Nazis and Polish policemen into the starving ghetto, where food allocations for Jews amounted to about 184 calories a day, required faith in G-d and a kind of righteous chutzpah (audacity) — attributes he learned from his Grandma Masha who told him, “Izaakl, rateve dich. (Save yourself.) You must survive, my precious child. Survive! Survive!” and then hid him under her bed when the armed SS in black uniforms — like drug-frenzied monster troops sent by Satan — marched up the apartment house stairs and broke down her door. They grabbed the old woman who was whispering tehillim (Psalms) and threw her down the stairs like garbage, a terrifying prelude to her murder — “One down, six million more to go.”

On April 19, 1943, the second night of Passover, the Nazis attacked the Warsaw Ghetto after forcibly deporting the elderly, the middle-aged, and the children to their deaths. The remaining Jews hiding in bunkers and attics in the Ghetto were teenagers and young adults, who resisted in a fight to the death. Eisner, who was 18 by then, fought alongside them and wrote about the Revolt — when a few young Jews with homemade Molotov cocktails, knives, a few guns donated by the Polish Resistance, and other improvised weapons fought back knowing they would lose, but taking heart in the knowledge that they were fighting for the sake of Jewish honor.

Eisner was a member of the Jewish Military Union ZZW, along with David Landau and others. Sara Eisner recalls attending the 60th Warsaw Ghetto Commemoration with her husband: “A man tapped Jack on the shoulder and called him ‘Jacek.’ Jack turned around and froze. ‘Duvid!’ said Jack to the man. They began to cry.”

At one point at the start of the Uprising, Eisner was sent up to the roof of the tallest house on the block — 17 Muranowska Street — to hang a hand-sewn blue and white flag, its colors copied from a Jewish tallit (prayer shawl) and duplicating the Zionist Movement’s standard with the Star of David. It was a Jewish flag.

![Jack Eisner Raising the Flag during Warsaw Ghetto Uprising by Alicja Kaczynska [Public Domain] via Wikimedia](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/599529_c4328f7088f14b95802ea704ca428a31~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_535,h_406,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/599529_c4328f7088f14b95802ea704ca428a31~mv2.jpg)

At that very moment, a Polish Christian woman named Alicja Kaczynska came out on her apartment balcony across the street from where the Ghetto flag was being raised and snapped a photograph of what she saw, although the figure of Eisner is too small to be clearly seen. The original photo, given to Yad Vashem in Israel by Sara Eisner many years later, was verified and confirmed as authentic by that respected and authoritative institution.

Moshe Arens, former Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. (1982), Israeli Defense Minister (1983), and Israeli Foreign Minister (1988-1990) wrote a book about the Ghetto Revolt called "Flags Over the Warsaw Ghetto: The Untold Story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising." In it, he describes that “ZZW fighter Jack Eisner was at his post next to the flags on the roof of Muranowska 17 when he saw German troops enter the ghetto,” noting that “Eisner and his friends… during the Uprising, participated in the fighting at Muranowski Square.”

Reached via email, Simcha Stein, Director of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum in Israel from 1996 until a few years ago, said, “Whenever I’m in Warsaw with groups (eight times a year), I’m telling Jack Eisner’s story at the Jewish cemetery. Jack Eisner should be mentioned due to what he did during the war and after it — as he took upon himself to be the torch to tell the story about the Warsaw Uprising.”

It shocked the whole world when this pathetic ragtag band of desperadoes held off the entire German army — which came at them with tanks, aircraft, machine guns, and flamethrowers in wave after wave of troops for nearly an entire month, from April 19 till May 16. When SS General Jurgen Stroop had to resort to setting fire to the entire Ghetto, burning the Jews alive in order to rout them — after some, though not enough, German soldiers fell and bled and died, showing themselves as very “UnSupermanish” — the young Jews died with smiles, some of them setting themselves afire and leaping out of buildings onto German tanks. Eisner, intending to escape through the sewer system as the battle neared its end, was captured by the Nazis.

On May 16, 1943, Stroop bragged to his Nazi bosses: “The Jewish quarter is no longer!” after screaming “Heil Hitler” and blowing up Warsaw’s famed Tlomackie Synagogue. It should be noted that a mere nine years later, Jurgen Stroop was no longer — he was prosecuted during the Dachau Trials where he was convicted of murdering nine American prisoners of war, and after that was tried, convicted, and hung for crimes against humanity by the People’s Republic of Poland.

Sheep To The Slaughter?

Eisner decried the old pervasive stereotype of Jews going like sheep to the slaughter. “It wasn’t true,” he said. “Every survivor was heroic in one way or another.”

He explained that his book "The Survivor" “wasn’t the whole story of the Holocaust and wasn’t the story of the shtetl… only the story of big city middle-class Jewish kids in Warsaw.”

Where did middle-class big city kids get the chutzpah and bravado to act so fearlessly in the face of such terror? Did the young Jack Eisner, untested and sheltered by his elders up until 1939, feel no fear going up against the Nazis? “I had a lot of fear,” he admitted, “I used to say to myself, ‘My God, I’m crapping in my pants. What’s going on with me? I’m a coward.’

"But I trained myself, with discipline, that I would still do what I thought was right, despite my fear. As an adult, I realized that the norm of human nature is such that, the more fear you have, the more you’re courageous. People who see danger and have no fear are not thinking.”

I wanted to know why the older people did not want to fight back too. Were they cowards?

“No,” Eisner explained. “Not at all. The parents were used to different systems of resisting Jewish persecution, systems that evolved through many centuries of persecution and served the Jewish people well. What were these systems?

"Number one; compromise with the enemy. Number two; negotiate with the enemy. Number three; bribe the enemy. Number four; sacrifice the few for the majority. Last point, educate your children and, in time, the tyrant will pass.”

None of these strategies applied to the Holocaust, which Eisner described as “unique in Jewish history because here, for the first time in 2,000 years, the old systems didn’t work.” His father, an educated gentleman, escaped into his books, reading up until the last moment when he was shoved into a cattle car.

“My father,” Eisner pointed out, “symbolized a million fathers. He found himself shocked and stunned because he had no one to negotiate with. He had no one to compromise with. He couldn’t bribe these oppressors; even if they took the bribe, they still did what they wanted to do. He couldn’t sacrifice the few for the majority; they wanted everyone. He couldn’t educate the children and mark time; the children were the first victims; they had the least chance for survival. He wasn’t facing oppression, discrimination, or persecution. He was facing annihilation. What did he do? What would your father do? My father collapsed, withdrew, isolated himself.”

Love And Romance During And After The Holocaust

When asked about the teenage romance described in the book, Eisner was eager to explain. Some critics were uncomfortable seeing this included in the book because this was a Holocaust book, and later, a Holocaust movie. Was this some kind of inappropriate attempt to schmaltz things up, Hollywood-style?

Halina, the lovely young woman who had fought alongside Eisner in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and captured his heart, was ultimately captured and used, like other young and pretty Jewish girls, as a sexual object of pleasure for brutal Nazi soldiers. After reconnecting with Eisner briefly after liberation, she died tragically from internal injuries inflicted by repeated rape.

“I think one of the great tragedies of the Holocaust was that hundreds of thousands of young, beautiful relationships were interrupted and destroyed,” Eisner pointed out. “There were tens of thousands of boys like Jacek and girls like Halina, tens of thousands of such desperate love stories.”

Eisner described the critics as thinking about the Holocaust “in terms of going to the synagogue, saying el maleh rahamim or kaddish… a spectacle of six million martyrs for history, as if all six million were walking, thinking only how to preserve history. Thousands of young people, myself included, had the energy to survive a concentration camp because we dreamed of finding back the one we loved. Can you understand that?” he asked.

At the time of the interview, there was no way to know that, at 60, he would meet a 30-year-old Jewish woman from Europe named Sara, who bore a remarkable likeness to Halina; or that after a fairy tale romance, the two would marry — first in a 1987 civil ceremony, and two years later in a religious ceremony performed by Chief Rabbi of Israel Yisrael Meir Lau, with Jack’s friend from the Warsaw Ghetto Simcha Holtzberg — “The Father of the Wounded Soldiers” — serving as Jack’s witness.

Neither was it possible to know that they would live happily ever after in Israel, although according to Sara, Jack never made aliyah; “he was too proud to be an American and wanted to die as one;” or to know that in 2000 they would move to Cannes, on the French Riviera, still living happily ever after — until the return to New York and unsuccessful medical treatment was followed by his death.

Years later, speaking to me, Sara would recall that her husband “believed in the Jewish tradition and went to the synagogue to ‘end his week.’ I got a feeling that he was on a constant lookout for members of his family. Perhaps someone did survive and was living in A, B, or C town, somewhere in the world? In synagogue, he never stood still, he would move around, look at people, study their faces.”

Long story short, this second marriage gave Eisner 16 years of blissful happiness. For Sara, even years later, it would be a bittersweet memory. “There is no such thing as a statute of limitations on grief. When I lost Jack, I understood that I would never be whole again, because he was my other half,” she said. “I say a prayer for his soul on a daily basis. Before I do something, I usually ask myself, ‘Would Jack do this?’ I remember just before he got so sick that they had to connect him to life support, he told me, ‘Do not fear, I’ll always be with you in your head and in your heart. You’ll do just fine — do not be afraid.’”

American-Jewish Commission On The Holocaust

After completing his book, plus the play and movie based on the book, Eisner had found his voice and the courage to speak truth to power, and so embarked on a new project.

He wanted to know what he did not know when he was trapped and tortured in a series of concentration camps. Like all the other poor souls who were beaten, starved, and subjected to ghastly medical “experiments,” with the worst victims gassed and burned, he had believed with his whole broken heart that if the free world would find out what was going on, surely they would move heaven and earth to stop it!

The American government knew, certainly the State Department knew, and yet endemic antisemitism informed their refusal to help rescue Jews, to bomb the train tracks to Auschwitz, or to facilitate rescues to be carried out by private citizens.

Eisner began asking about the behavior of American Jewry during the Holocaust — a question simultaneously delicate and hard: What were the Jews in the U.S. doing while their fellow Jews were being systematically slaughtered in Europe? Could wartime American Jewish leaders not have rescued at least some of the victims from the gas chambers and crematoria? Were the reports coming out of Europe not taken seriously by Jewish organizations, and if not, why not? And if they were, where were the all-out valiant efforts to save the doomed Jews of Europe?

Eisner set up the American Jewish Commission on the Holocaust, staffed it with high-level upstanding individuals, and funded it with serious money. Chaired by former Supreme Court Associate Justice Arthur J. Goldberg, with Professor of Political Science at CUNY Seymour M. Finger serving as research director, the Commission’s purpose was to look into the actions, non-actions, and attempts at action by Jewish leaders and then produce a report on its findings.

Bitter controversy arose when some organizations refused to open their records, ostensibly fearing a public airing of shameful back-turning, eye-closing, ear-clogging behavior by well-known and well-connected big machers in Jewish America who “could have would have should have” done something to help. The Commission, starting up in 1981 with everyone agreeing to let the chips fall where they may, was dissolved in 1983. Eisner, seeing the goal of truthful inquiry doomed to producing a whitewashed watered-down report, refused to continue funding it. Goldberg, with a lifelong record of distinguished, untarnished service and integrity on the line, could not stand up to pressure from certain Jewish groups.

Eisner concluded from what he had learned in the study, that “American Jews were afraid,” but added that there were some who were not so afraid. “Orthodox Jews helped more,” he stated. “Why? Because they had a greater commitment to what was morally and ethically right. They compromised less. It was, for them, a kiddush Hashem to rescue fellow Jews.”

The official reason for the Commission’s demise — written up in emotional tones in all the Jewish newspapers, and less heatedly in the mainstream press — was bitter infighting, shame over what might be revealed about American Jewish leaders, and anger over Eisner closing his checkbook.

But as Eisner would privately reveal much later, all of that was not the real reason for the Commission’s disbanding. According to him, during the Commission’s investigation into the activities of Jewish organizations vis-à-vis rescuing the doomed European Jews, something far more secret and sinister came to light — that the American government had brought to the U.S. a number of Nazis, especially the scientists, to continue their experiments in American laboratories. This truth — which is public knowledge today — was not supposed to come out at that time or any other.

“People” visited Eisner in his Empire State Building office and behind closed doors, asked him if he wanted to continue to run his successful import/export business. These “people” were not mob hit men delivering an ominous message from real life Don Corleone types à la “I’m gonna make you an offer you can’t refuse.” These were messengers from the high reaches of government with infinitely more power, muscle, and absolute legal authority, delivering the same ominous message with its implied threat.

The very next day after these “visitors” left, Eisner dropped his support for the Commission and called off his efforts to continue any further investigation. The information uncovered about Nazi scientists, many of them guilty of atrocious war crimes, brought to the U.S. to secretly work on advanced weaponry, was not known by the American people at the time.

Eisner had walked out of Nazi hell due to three things, “a combination of luck, courage, and the grace of G-d.”

He had learned that to read a man’s face wrong meant certain and immediate death. What he must have read in the faces of those “people” who strode into his offices was grim, grave, and deadly danger, though perhaps disguised with a gentleman’s handshake and smile — as he was told to make a “choice.”

Jack Eisner Meets The Angel Of Death

At the end of his life, Jack Eisner was diagnosed and treated for colon cancer at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. After arriving back in New York in August 2003, he was admitted to Memorial Sloan Kettering where doctors gave him more chemotherapy. Growing sicker and weaker, he came face to face with the malach hamavet (the Angel of Death) — not another Nazi Agent of Death sent by Hitler, but this time the true Angel of Death, sent by G-d to gather Jacek Zlatka to his people. And all of his people were survivors like him until they were murdered:

Grandma Masha who hid him under her bed as the Nazis were marching up the stairs;

Halina, his 19-year-old childhood love;

Hela, 15, his sister and food smuggling partner in the starving ghetto;

Young cousins — 30 of them, ages 2–13;

His father, enslaved at Majdanek, liquidated with the entire camp of thousands by the Germans;

The brave young Jewish fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising;

Whole neighborhoods, cities, countries, continents of Jews, erased from the world.

May G-d avenge the blood of six million murdered Jews. Baruch Dayan HaEmet — Blessed is the Judge of Truth.

Beth Sarafraz is a freelance published writer living in Brooklyn, New York. Click here to read more of this writer’s work in The Jerusalem Herald.

Comments